This year’s reflection is about stories.

The stories we are told, the stories we aren’t; the stories we believe and the stories we dismiss; the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we tell children; the stories that are myth and the stories that misunderstood.

Stories we tell ourselves.

I think we tell ourselves stories all the time. Narratives we weave to explain and understand the world around us, especially other people.

Like this.

Imagine you’re sitting at a stop light and you don’t realize that the light has turned green. The person in the car behind you honks to let you know the light has turned green. You get defensive; maybe say aloud “Have some patience!” (Or perhaps something more colorful).

Another day you’re at a light and the light turns green and the car in front of you doesn’t go immediately. Do you “have some patience!”? Or, like me, do you get frustrated and perhaps tell yourself a story about the incompetence of the person in front of you. “Not paying attention- too busy texting to drive.” Or, if you’re honest, maybe your story is a little more specific: “those teens are always texting”; “that old lady needs to get off the road”; “those people need to learn to drive”…

We tell ourselves stories all the time, usually without thinking about it. And I think the stories often reveal our biases (explicit and implicit) and certainly our assumptions. Sometimes it’s just a story or a fleeting thought known only to ourselves. Sometimes we catch ourselves as the story forms – recognize the bias – and rewrite it in the moment. And sometime that story has larger implications-

an applicant not hired, a student suspended, a gun fired.

Those are the stories I’m thinking about today.

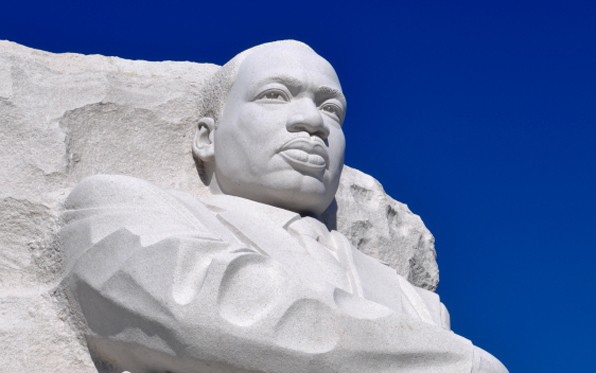

Stories that are representative

We celebrate and honor Martin Luther King, Jr. as a singular, extraordinary man. But we also honor the people and the movement, the struggle and the sacrifice he represents. He has become more than just his own story. This past year, we have come to know the stories (or rather the tragic end of the stories) of Mike Brown, Eric Garner and Tamir Rice. They are both singular and representative of the anger, frustration, fear and anguish of an unjust system. These men became more than just their death. And their stories must be told- no shouted- because there are so many similar stories never even whispered.

Stories that are “color blind”

But there is one story about race we hear all the time. I believe that one of the most destructive race stories told in the United States is the ideology of being colorblind. This myth is often told through the misinterpretation (at best) of King’s words: “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Not judging someone by their race is not the same as not seeing their race. Colorblindness erases an important part of many people’s identity. And ignores reality. And is paralyzing.

If we believe the mythology of colorblindness, then we cannot actually talk about race even in the most basic sense. And we certainly cannot address racism. My eyes are brown; my hair color changes depending on the dye I use; my skin is white. If you don’t see those things, you don’t see me. Ignoring people’s identities is not progress. Progress is seeing a person for their full self and treating them with respect and dignity. Progress is recognizing the ways that racism is present in our systems and addressing them. Progress is telling the story of racism in this country with nuance and texture and truth.

Stories that are “good” or “bad”

Stories are often presented as dichotomy, either someone is a good person OR they are bad. This is especially true in narratives about racism. For example, if we name our concerns about racism in law enforcement, then we are interpreted as saying that all police officers are “bad.” The obligatory counter story “there are good police officers, too” is recited. But when it comes to bias (and most issues really), good and bad are completely beside the point. It doesn’t take a person of ill will to perpetuate racism. “Good” police officers have bias. “Good” teachers have bias. “Good” (fill in the blank) have bias. Goodness (whatever that means) is not some sort of protective anecdote for racism. That narrative is completely unhelpful. Certainly there are officers who are undeniably engaging in racist practices and there are police chiefs who are taking real leadership on these issues. But the real story is about systems. And this “story” about goodness is, simply put, getting in the way of addressing those systems. As Kareem Abdul-Jabar wrote recently: “The police aren’t under attack. Institutionalized racism is.”

Stories that we tell children

The stories that we tell the children in our lives about race and racism usually depend on, well, race. The child’s race and the adults. Kids of color often get “the talk” about race. Or rather, many talks about race. This is often not a choice for their parents, even when it’s desperately not the story they wish to tell. Yet, white children with white parents often don’t get told a story at all.

I know I’ve written about this before. But it is something that comes up all the time: truly concerned white parents of white kids who worry that talking about race will make their children racist (see: Stories that are colorblind). The thing is that I’ve never heard a parent say “It is important to us to raise our children in our religious faith tradition, but we’re not actually going to teach them what we believe, we’ll let the media do that.” Or “I want my child to be polite and use ‘please’ and ‘thank you,’ but I’m not going to actually tell them that.” I’m truly not being snarky; I just want to make the point that we instruct our children all the time on what’s important to us. And when we don’t explicitly talk to them about race and racism, that story is loud and clear.

Stories that lack nuance

We don’t seem to like nuance in this country. Or at least the media certainly doesn’t. And that’s a problem when we’re trying to address systemic racism. The story of racism in our country in nuanced. Racism isn’t just bold and blatant; it’s implicit and subtle. It’s not just white supremacists; it’s white supremacy. It’s not just black and white; it’s the common and distinct experiences of discrimination for all people of color, bi-racial and multi-racial people. Racism is intrepid, and shape-shifting, concrete and ephemeral, personal and institutional, embodied in individuals and in systems.

Stories that are unfinished

The story of Martin Luther King is not just biography, it is myth- he is larger than life.

Embedded in the myth is the idea that we’re done. That he had a dream and now we can celebrate. The real story, all around us, is that we’re not done. Yes, the civil rights movement accomplished many things. However, we still have attacks on voting rights, we still have unequal and disparate treatment in schools, we still have injustice in the criminal justice system, we still have brutality and bias in law enforcement and we still have a dream to deliver.

Today, let’s remember and celebrate the man, the myth and the movement. But this story is not written. It is being written. This story is not about the past. This story is about today. And we are the authors of that story.