The U.S. Department of Justice and the U.S. Department of Education just released an important document: guidance on school discipline that reaffirms what many of us have been concerned about for years- the disproportionate discipline rate of students of color and its contribution to what has been called the “school to prison pipeline.” It is no small thing to read a document from the federal government which states in plain language that “discrimination in school discipline is a real problem. ” It included data from the Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) that found African-American students without disabilities are more than three times as likely as their white peers to be suspended or expelled from school and that “the substantial racial disparities of the kind reflected in the CRDC data are not explained by more frequent or more serious misbehavior by students of color.”

This is important. This is recognition of the systemic nature of racism and its real consequences.

This makes clear that it is an issue that spans the country: across states, across both big cities and small towns, across school districts, across economic status.

And it is important because it lays bare the myth that racism is simply an act of “bad” individuals. No one can suggest that every school system across the country is made up of hardened, blatant racists who are intentionally discriminating.

No, we must understand that racism is much more pernicious than that.

Let me share a story:

A few months back I was visiting S at school during lunch. It was the end of the lunch period and the first grade children were lining up. The first child in line was a young African American boy. He was a little fidgety, but no more than any other first grader trying to stand still in line. The lunch monitor turned around, locked in on him and his fidgety body, and told him to get out of line and to sit at a table for the kids who “got in trouble.” He tried to protest that he didn’t do anything. The lunch monitor ignored his protests, just as she had ignored the two white girls talking and giggling behind him in line. The teacher came and his “behavior” was reported and once again he attempted to protest and was rebuffed. And then, as he realized it was futile, his shoulders slumped, his head dropped and a look of resignation settled into his face. It was a resignation that it didn’t matter what he said and it didn’t matter that he knew he hadn’t done anything wrong. It was resignation that things were often not fair, not for him. I watched his face transform in a moment from indignation to resignation and it broke my heart.

Now, some of you will read that paragraph and immediately recognize the scene. You can see the moment and the look. And you understand.

Others will read it and the disagreement or justification will start in your head. The “buts” of argument. “but… you don’t know that was about race.” Or “but… being a lunch monitor or teacher is hard, they miss things sometimes.” Or “but… that’s just one situation.”

I don’t blame you. You’re right. I can’t prove to you that race was the heart of that encounter. And the lunch monitor? She’s not a “bad” person. In fact, if asked I am positive that she would protest and truly believe that race was not a factor. And it was just one situation, one moment.

The reality is that those single moments can almost always be “butted” away. And they are. All the time. Unless the presence of racism is blatant, it is so easy to dismiss (and even sometimes when it is blatant, we still do our best to deny).

And that’s how you have undeniable evidence of racial disparity in our schools without the recognition of individual acts of racism or identifiable racists.

And that’s because as a country as a whole, and in our media, we don’t understand racism in its complexity.

Racism is systemic, institutional, pernicious, deadly, engrained and unconscious. It is hypocritical and inconsistent: sometimes sneaky, sometimes bold, both subtle and blatant. It is empowered when ignored and emboldened when denied. (And so it thrives).

And racism is stubborn and entrenched because it requires deliberate engagement to be dismantled.

That’s why the Department of Education’s Guidance Letter is both so important and so meaningless. It states the issue so plainly but its remedy is not. Because, until everyone connected to the school system is willing to look hard at themselves and ask truly tough questions, and until each school staff person is willing to entertain the notion that they are engaged in the perpetuation of a racial inequity, whether conscious or not, those statistics will remain.

But this issue isn’t just about school teachers or staff. And it’s not an indictment. I am privileged to know and work with many dedicated, reflective educators committed to equity, including those at S’s school.

No, it’s about all of us. The entire community has to hold ourselves accountable, examine our own prejudices and ask ourselves hard questions. Who do we see as the “troublemakers?” How do we define “good” schools? How do you talk about “those kids” or “diversity”? Do we explain away racial issues with vague notions of good intentions? Will we be honest with ourselves? Will we require others to be honest as well?

If we do not, then we have chosen resignation that racism will continue to systematically disenfranchise our kids of color.

And ultimately here’s the point: the boy in the cafeteria? He was right. He didn’t do anything wrong. But I did. I watched it and didn’t speak up for him. I didn’t say anything because I felt uncomfortable interfering. I told myself it wasn’t my place.

That, too, is how racism is perpetuated.

So I am holding myself accountable.

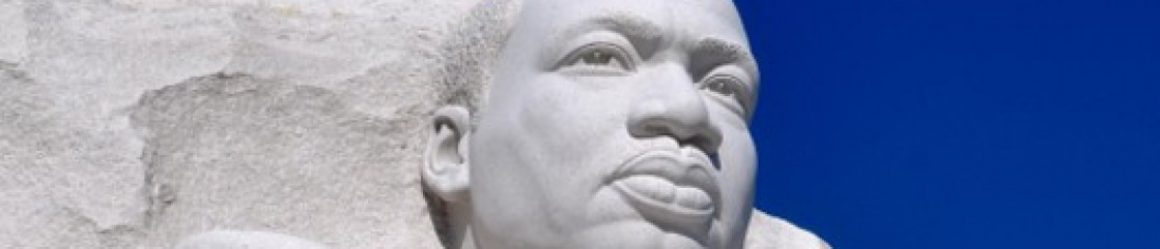

This MLK Day, I refuse to be resigned.

One thought on “Martin Luther King Day Reflection 2014”