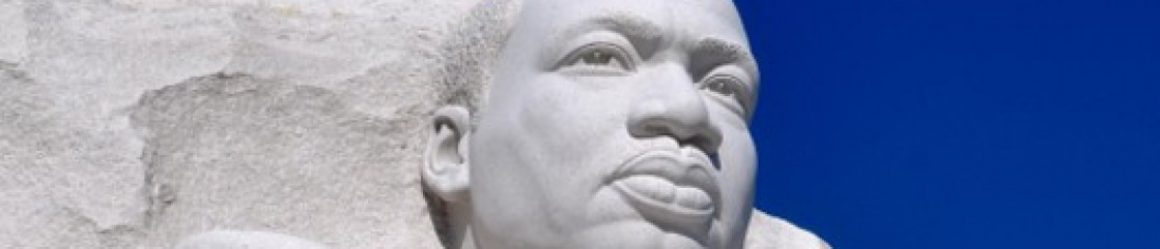

For many, Martin Luther King, Jr. Day is a day to reflect not only on Dr. King’s legacy and accomplishments but also to celebrate the accomplishments of the civil rights movement and all its heroes. It is also a time to reflect on “how far we’ve come,” and hopefully, where we still need to go.

For me the where we need to go is a very important part of the reflection. In the past year, I have been thinking a lot about my responsibilities to help my daughter understand race and racism in age appropriate ways. I want to make sure that she (and now, the baby on the way) understands the history and the legacy as well as our role in continuing to fight against bias and for civil and human rights. As adults, I think the tendency is to think that’s a conversation for when she’s older, but I know that she is (and has been) forming her understanding of race throughout her young life.

I have been thinking about this even more this year, I think in part because of some emails that I received last year after my MLK reflection about teaching S about everyday heroes.

One email I got was from a dear friend from college who identifies as Africa American and has two young children who are also African American. She spoke very frankly about the additional struggles of raising her children and the ways that race and racism play out in their young lives and how hard it is for her.

I also received a few responses from good friends who identify as white and have young white children. They were concerned about how to raise the topics of race, discrimination and racism (either historically or present-day) for fear that if they introduced talked about different races or racism that it would actually foster racism or introduce those ideas to their children.

To me these different responses, all sincere and heartfelt, show clearly the way that race and privilege play out in the United States. For my friend of color, there was no choice. Race and racism are always present and she and her spouse have to engage their children in those conversations regularly, whether they want to or not. White parents, by and large, have a choice about whether to discuss race (or feel they have a choice) and, as a result, don’t talk about race with their white children. In fact, parents of color are three times more likely to discuss race than white parents and 75% of white parents never, or almost never, talk about race. (NutureShock, p. 52)

And that’s what has been on my mind. How can we get more white parents of white children (I am using that distinction purposefully, because not all white parents have white children and vice versa) talk to their children about race. I write this partly out of selfishness, because I want and need allies in this conversation and because sometimes it feels really lonely (not because I think I’m the only one struggling with this or thinking about this, but because, just like the actual conversations about race, I find there is very little discussion amongst parents about having race conversations… if that makes any sense).

So this year, I am especially writing to and for people like me: white parents of white children (as well as anyone who has white children in their life).

Here’s the thing, we live in a society where generally there is very little conversation about race. And many people hold a sincere belief that if we don’t talk about race or differences then that in and of itself will end racism (the colorblind philosophy).

In my work and in my personal life I hear things like “my kids don’t even know what race is” or “my kids don’t see color” often. Well, of course, kids do see color. One of the first things we teach our children is to distinguish by color- sort yellow from red from blue and distinguish items using color as a cue (“my yellow truck, “that blue blanket,” etc.). Why would we assume that kids would stop distinguishing color when it comes to people? Children do in fact see that different people have different skin color. What I think most people really mean to convey in these statements is a sincere belief that the social construction of race has not yet seeped into their children’s heads- that their children don’t make judgments about race. I get that. I want to believe that about my own children.

But if we never talk with them about race, how will we know?

In fact, I’ll take it one step further and say that if we don’t talk with children about race then we can assume that they are in fact making assumptions based on race.

Now, at this point, people might say “what?” or “not my child!” or stop reading because now I’m impugning your child.

However, the research in child development makes it clear. And from a gut level, I think it makes sense. Has your child ever come to you and started talking about something that you know you never have talked about or introduced? (Like when S started talking about Justin Bieber. I know that didn’t come from us). Our kids are getting a lot of messages from everywhere- friends, media, school, environment, pictures, etc. And through those vehicles, there are a lot of messages about race. A lot! And usually not the messages we want them to get.

So, if we’re not providing counter-messaging, then…

Studies show that leaving kids to figure it out on their own often results in the very bias and prejudice white parents are worried about. You might have seen some of these studies yourself- they recently did a series on CNN (see link below). And the parents were always so surprised that their white child showed racial preferences and internalized messages that their race is better… but then they admit that they never talk to their kids about race.

Dr. Phylis Katz, who has conducted a large number of research studies on race attitudes in young children (like from 6 months of age young and up) has written: “During this period of our children’s lives when we imagine it’s most important to not talk about race is the very developmental period when children’s minds are forming their first conclusion about race.”

So why don’t we talk about race? In addition to the concern that we’ll inadvertently introduce racist attitudes, there is another reason. Put plainly, we’re uncomfortable. We don’t know how to talk about race and are afraid that we’ll say the wrong thing.

In the book NutureShock, Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman address this exact topic in the chapter “Why White Parents Don’t Talk about Race: does teaching children about race and skin color make them better off or worse.” (It’s a great book! ). In the chapter, they highlight an interesting study in Austin, TX where white parents were recruited for a study about racial attitudes in children. Once in the study, parents were asked to explicitly talk to their children about interracial friendships (saying things like “Some people on TV or at school have different skin color then us. White children and Black children and Latino children often like the same things even though they come from different backgrounds.” And so on). Well, several of the parents dropped out rather than talk explicitly about race, even thought they knew it was a study about racial attitudes. Then, it turned out that several of the parents who stayed in the study didn’t really follow the instructions. They talked with their children but in a more vague way, saying things like “everybody’s equal” or “under the skin, we’re all the same” – general phrases that didn’t specifically call attention to racial differences. These kids didn’t show any improvement in racial attitudes after the study. But for the few parents who really did talk openly about race, all of those kids greatly improved their racial attitudes. (p. 47-52)

So, it turns out that not only do you have to talk about it, but you have to talk about it explicitly. I know this was an important reminder to me, I have definitely used the vague “everyone’s equal” language with S before.

So, children need explicit conversation. And they need to be engaged, even when they say something that embarrasses us. Even though our instinct may be to shush the child or ignore them. Because then, we’re back to silence again and the message that the topic is unspeakable (and therefore, bad). I’m sure we’ve all been there- our child loudly points out some form of difference and we cringe. (It happened to us recently around age differences. We were talking about a teacher and S said “She’s an old lady.” Our first instinct was to say “S, that’s not nice.” And then we had to circle back and say “You’re right, people are all different ages and she is older than your other teachers. And people don’t usually like to be called “an old lady” like that.”)

There’s so much more interesting research and studies to share, but I have to remember that not everyone finds this stuff as fascinating as I do. Instead, I posted some links and resources below- things that I’ve found to help me have those conversations with S.

The bottom line, and what I am focused on this MLK day, is that I have a responsibility to address race, not only with adults, but the young people in my life. And when I avoid doing so, I am making a choice out of privilege. A choice my dear friend from college does not get to make.

So, here’s my reminder to myself:

Feel uncomfortable. Do it anyway.

Not sure what to say? Start talking.

Scared of what they’ll ask (‘cause they could ask anything)? Dive on in.

Feel too hard? Keep on trucking.

I hope that you’ll join me and we can support each other and share our successes and failures.

Not just on Martin Luther King, Jr. day, but it’s a good day to start (or continue or renew our efforts).

Sending my love and wishing you a reflective day,

Beth

Research, articles and videos:

The Bronson/Merryman Newsweek article: http://www.thedailybeast.com/newsweek/2009/09/04/see-baby-discriminate.html

http://library.adoption.com/articles/young-children-and-racism.html

The CNN study I mentioned:

UPDATED: AC360 Series: Doll study research

Panel discussion: Kids and race

Tips and resources:

http://www.adl.org/education/miller/q_a/answer8.asp?sectionvar=8

http://www.parenting.com/article/5-tips-for-talking-about-racism-with-kids

2 thoughts on “Martin Luther King Day Reflection 2012”